Genii Magazine

Interpreting Magic

David Regal

Review by Francis Menotti

David Regal is not human. Over the hours, no—days—of thoroughly digesting the more than 500 pages of his freshly released tome, it is evident that the man is part elfish imp, part unstoppable robot, and a fully whimsical creative genius with the witty demeanor of a mischievous Terry Pratchett character. If one is looking for another procedural, academic textbook featuring the here’s-a-trick, here’s-the-method format, they will be disappointed. This is a journey through magic and its construction and its betterment. It is a collection of time-and experience-tested thoughts, cleverly disguised in tricks, moves, routines, essays, and an impressive number of interviews with many of today’s top minds in magic.

Typical behavior for opening a book for the first time might be to gravitate to the table of contents and see what lies ahead. Don’t. Part of the joy of this reading experience is the discovery process— the surprising plots, the eureka bits of wisdom, and the incredible lineup of conversational interviews that the author has secured and walks us through so comfortably that we feel as though we, too, are in the room. In an essay later in the book, he even discusses this phenomenon in the “Power of Not Knowing,” articulating the increased enjoyment that can be gleaned from withheld information and intentionally unsatisfied curiosity.

With each turn of the page, Regal guides us through his thought process, and his vast experience as a writer, director, creator, consultant, and performer of magic, illustrating his points with commercial but unique effects. In turn, he punctuates said effects with stories and tidbits from his own experiences onstage, or uses them as allegory to support the wisdom we learn from the 28 armchair conversations with his fellow masters of the craft.

Let’s crack the cover. An unsurprisingly charming introduction by Michael Carbonaro sets the tone, immediately giving anecdotal credence to everything that follows. Regal’s own succinct preface belies the fact that we’re in for a lengthy read, as he dives right into the first of seven sections: “Cards.” Whether one seeks more pasteboard pieces for their repertoire or whether their mantra is “not another card trick,” the opening effects are quick, fun, and well-described with little to no sleight of hand. Still, they have some lovely beats that are carefully staged and structured. Leading off the parade of effects, “The Magicians” is a quirky transposition of Kings and selections with a light anthropomorphic presentation and a little reminiscence of Larry Jennings’s “Visitor,” only more ergonomic in its handling.

We learn quickly of the author’s self-admitted affinity for Ace-cutting routines, beginning with “Straight Face Aces,” a maniacal series of admirably brazen bluff pick-ups and ditches that are not for the feint of guts. He immediately follows with a much less intimidating Ace-cutting routine as though to ease our fears that the entirety of the material might feature equally high-risk methods. Repeatedly throughout the book, Regal rewards his readers with “safe” yet still clever routines every time he pushes our comfort zones with others that make our palms sweat. This dichotomy of boldly challenging versus cleverly simple techniques sheds some light on Regal’s whatever-it-takesfor- the-best-effect mentality that is evident in every piece within. To close out his Ace-cutting series, Regal regales us with an amusing anecdote of his one and only meeting with Ed Marlo, a follow-up story of verification from Johnny Thompson, and a wonderfully blunt method for what Thompson assured was Marlo’s favorite method for “Cutting to the Aces.” It’s in these first asides that we get a sense for Regal’s engaging narrative style that draws us in and teases us to skim past the tricks to get to the essays and interviews. Don’t be tempted; the contents of the book, even if taken out of order, all complement each other for a thoroughly enjoyable read.

Scattered, or rather meticulously placed, throughout the volume, Regal’s essays impart apropos nuggets of wisdom stemming from his onstage and behind-the-camera experiences. These address storytelling and staging, the vitality of likability on stage, and the decision of how we wish to be remembered by the audience.

To paraphrase an example he discusses regarding importance of staging of props and how it can affect the audience’s experience—if the coins are too close together for a Matrix routine, the audience may not be as impressed when they travel. Just a little more distance between them, and the subconscious belief is that the increased distance is thus somehow more difficult, “more” impossible. The nuances of staging, structure, and conditions of any given effect make as much difference, per Regal’s philosophy, as the mastery of the necessary sleights.

Before delving into a brief overview of the rest of the book’s sections, let us address the Aronsons, Burgers, and Carneys of the interviews within. Regal structures said interviews in sets of three, alphabetically by subjects’ surnames, again showing an attention to detail even in the book’s layout as though it were a performance. The conversations cover topics from Barry and Stuart’s early days attempting street magic to John Bannon’s reductions of effects, Derren Brown’s upbringing, Angelo Carbone’s take on thievery in magic, Kevin James’s favorite creations, Teller’s “Shadows,” Michael Weber’s toothpaste, R. Paul Wilson’s broken ankles and “Svengali Decks,” and Rob Zabrecky’s grandfather. These topics are but a fraction of those discussed by so many other great names, and give a beautiful balance of brilliance and humanity to our art form. Regal’s relaxed banter and quips with each of the subjects also humanize them and peel back eye-opening layers of what goes into making great magic and great magicians. If Interpreting Magic comprised nothing more than the interviews conducted within, it would be still worth its purchase price for its entertainment as much as its education.

The next several sections of the book take us through Regal’s original card moves, close-up magic, more card magic, Monte routines, his full set with a “Rainbow Deck,” and his decades of development of stand-up and stage material. In many of these, he works through classic plots but with not-so-standard props. Such it is with “Stones.” It’s a Coins Across-style effect executed instead with beautiful geodes and loose gems (and a particularly customized hold-out.) Similarly, Regal walks us through a wacky chairless Chair Test-type effect in his stand-up section, in which a prediction correctly identifies which of three people will be holding a beer, a ball, or a baby. You read that correctly, and it’s this type of outside the props-type of thinking that can’t help but inspire the reader to reconsider the status quo items that we as magicians tend to cling to for no particularly good reason. Still along the same lines, he reveals a utility prop with a multitude of potential uses: a seemingly standard paper cup that is an arts-and-crafts cousin of the Chop Cup, with a magnetic flap and a bit of thread that allows for switches, changes, appearances, and vanishes, all under the guise of an innocuous everyday item.

On a few occasions, Regal shows us his re-examination of old tricks and methods that he’s evolved since former publications. “There” is an updated, less cumbersome version of his 1999 piece, “There and Back.” Rather than the featured item being a borrowed ring that travels across the table through a bit of clever but involved chicanery, this version employs a much simpler method and gaff that the reader already likely possesses. Instead of transporting a borrowed ring, the traveling effect is with an initialed coin; so where the emotional investment in the effect may be slightly lowered, the practicality of its performance is notably increased. Not that one is necessarily better than the other, just that it’s a great exercise never to stop working on the pieces that we consider fully done.

He brings us along similar journeys of revisiting methods and plots with “Glass & Gold”—an amazing but sleightless vanish and reproduction of a borrowed ring from a shot glass, and again with “Sticker Shock,” a variation on Regal’s marketed trick “Sudden Deck.” In this rendition of the appearing deck, the performer introduces a boxed pack of blue cards, removes them from their case, then applies sticker labels to the empty case that transform its appearance to that of a red case of cards. Upon such application, the box is re-opened to reveal a normal full red pack of cards. The two methods Regal describes are simple and as attractively fun as the trick is to perform.

In one more instance of retooling old effects, Regal plays at the classic Harry Roydon routine “Crazy Cube,” a die trick that probably every reader has owned or at least seen at some point. It’s questionable as to whether this found its way into the book for any reason other than to reinforce the notion to keep improving old methods, and it is decidedly more to fool fellow magicians than to present to a layperson, but its method is bald simplicity and an amusing illustration of Regal’s creative problem-solving skills. That, and he uses the same office-supply technique here as he does a number of other times throughout the book, each time in different ways.

His section on Monte effects show his commitment to creatively addressing arguably tired plots and his unique ability to breathe fresh life into them. As one who hasn’t much interest in the Three Card Monte plot, I ,for one, will be playing with the fast-paced, multi-phased “Find the Dude” in which the money card is fully destroyed and yet reappears whole at the conclusion. To that end, all of the material is worth a read, even if it does not initially seem to fit the reader’s immediate magical interests.

This brings up the interesting notion of forced creativity, or more precisely creativity within parameters. Regal’s “Valentine Trick,” “A Ring Routine,” and “The Rainbow Set” all share the constructive impetus of creating to solve for a specific self-imposed challenge. The “Valentine Trick” was born out of necessity to perform a specific Valentine’s Day show. “A Ring Routine” was one way of Regal satisfying his desire to perform a full set without any cards or coins (and does so admirably). And “The Rainbow Set” was his challenge to perform a full set featuring a Rainbow Deck. These pieces stand out as magical etudes, excellent to study more for composition perhaps than for putting into one’s repertoire. But the lessons in construction of all three are invaluable in helping the reader accomplish the intent of the book’s title.

Two quick worthwhile mentions fall in the Stand-Up & Stage section. “Doctor, Doctor” has the ability to be both a blessing and a curse to find its way into nearly anyone’s repertoire with little preparation and virtually no difficulty. It’s a delightful potential opener in which the audience freely chooses from a list of 68 most “glamorous jobs in the world.” The payoff is a quick and cute revelation of the correct prediction by way of a roll-down poster in front of the volunteer’s body. As easy as this is to pull off, it is again the construction and recommended staging Regal describes that make it such a strongly commercial piece.

Finally, the other aforementioned effect is a credit card vanish and reappearance inside a zippered wallet, inside a cigar box, inside a closed bucket, inside a chained and locked trash can. A little Rube Goldberg, a little Gaëtan Bloom, and a little Tommy Wonder, this object-to-impossible- location is a wonderful combination of absurdly comedic presentation and an equally enjoyable method. It’s a fun read and, I can imagine, an even more fun piece to perform.

In this massive collection, the reader will find material that anyone can do, that some people can do, and some that really only the author should probably do. The necessary skills and props vary greatly. None of the techniques are particularly knuckle busting, but they can often be bold. And the items needed for performance range from a pack of cards to specially cut glass bottles, 100 envelopes with 100 force cards, or a length of chain and a trash can.

This isn’t a shopping cart full of items to add to one’s repertoire (though many pieces certainly could fit the bill). This is a call to all lovers of the craft to better it by way of the book’s title—interpretation. It’s a valuable, highly recommended piece of magic literature from which every reader can gain inspiration.

INTERPRETING MAGIC

Review by Michael Close

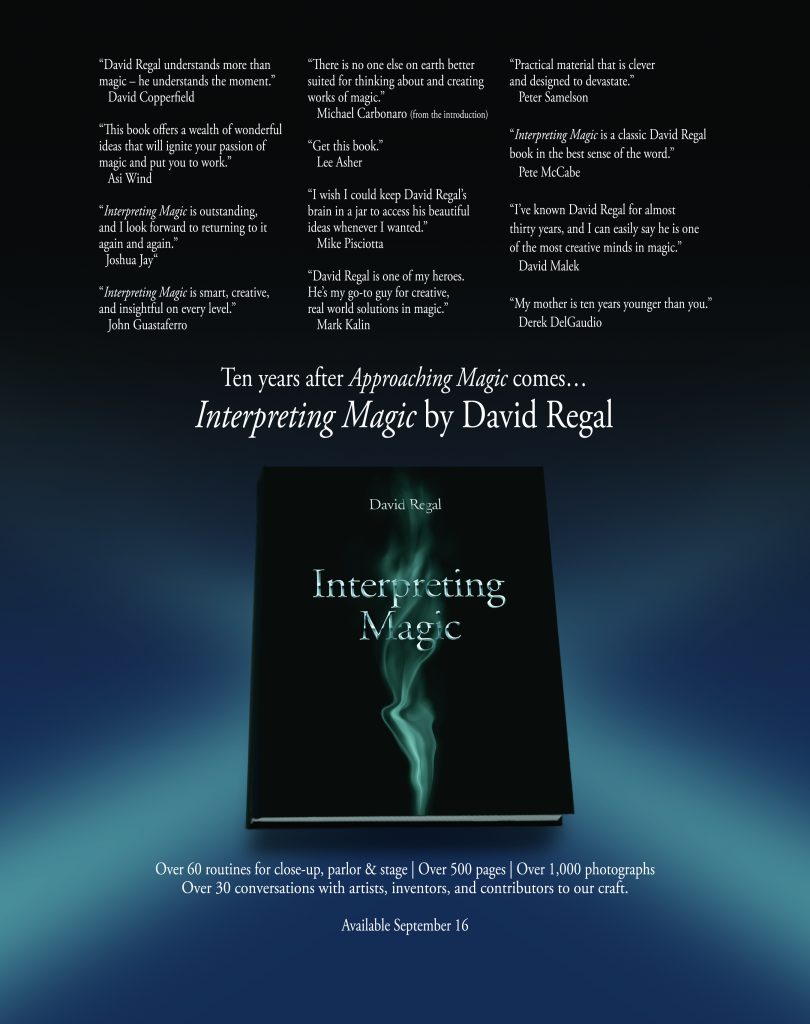

It has been ten years since David Regal has gifted us with a big book of magic; that book was the wonderful Approaching Magic. His new book is Interpreting Magic, and it, too, is wonderful, with a wide variety of clever routines of all types (suitable for close-up, parlor, and stage), insightful essays, and interviews with a who’s-who of top creators and performers. There is literally something for everyone here.

If you want to skip the rest of the review and head right to David’s website to order the book, here’s the bottom line. If this book only had the magic routines, it would be worth the price. If this book only had the essays, it would be worth the price. If this book only had the interviews, it would be worth the price. To get all three, packed into a beautifully produced, 565 page book is a gift. In fact, it’s the gift that keeps on giving, because I know you will return to it often to find magic you previously overlooked and to remind yourself of the wealth of useful information contained within.

David Regal performs regularly at the Magic Castle and makes infrequent convention appearances. What has kept him off the magic radar is his work as a consultant for television and movies. In particular, he has been the driving magical force behind the popular hidden camera/prank show, The Carbonaro Effect, which is currently taping its fifth season.

I am a longtime fan of David Regal’s work. He has a knack for creating well-constructed, sneaky routines. As I read through them, I almost always encounter something that makes me think, “Ah, that’s clever.” In addition to the craftsmanship shown methodologically, what I really appreciate is that every routine he publishes has a “hook,” a premise, some bit of unexpected whimsy that draws the spectator into the proceedings. David also emphasizes scripting; each piece has a thought-out presentation. You might not (and probably won’t) use his words verbatim, but he offers a pathway that can aid you as you write your own script. A third important factor is staging; David understands how to elevate an effect (and conceal sneaky stuff) through blocking and audience management. Even if you never perform any of his routines, you will learn a lot by studying how he puts them together.

Scattered throughout Interpreting Magic are essays devoted to topics such as the things I mentioned in the previous paragraph: Staging, Structure, and Conditions; Writing Magic; Magic in Motion; Method and Effect; The Power in Not Knowing; Examining Examination; The Human Element; Falling Down; and several others. All of this information is backed up by David’s years of experience as an improvisational comedian, a comedy writer for television, and a consultant/coach for many projects. The overarching priority, however, is given in the title: the need for magicians to be interpreters of the magic effects they perform. In the Preface he writes:

This book has many pages, but its intent can be summed up in a sentence: The surest pathway to good magic is through interpretation.

It’s strange that there is a need to point this out, as it is something that goes without saying in the case of all the other arts. No singer purchases the sheet music to a song, and thinks, “I’m done.” The singer is not done. The singer is just beginning, and the sheet music is a tool that allows the singer to begin.

That is what a magic secret is. It’s wonderful, essential, and just the beginning.

Secrets are a necessary component of magic. They allow a performance of magic to occur, and as such are a means to an end, not the end. They give us a way in which to reach a desired aim, and the better secrets and methods provide pathways that allow our aim to be realized with elegance. The audience does not enjoy the secret, because the audience does not perceive the secret. All the audience can take in is the presentation of our intent. The decisions we make in the process of creating that intent become our interpretation.

How important is this idea of personalized interpretation? I’ll let you make up your own mind about that, but here’s a hint. Interpreting Magic includes interviews with more than thirty of the top performers and creators in magic today. I’ll give you a partial list. As you read through the names, make note of the fact that each and every one of these magicians has established an identifiable, unique performing style: Simon Aronson, Barry & Stuart, John Bannon, Gaetan Bloom, Eugene Burger, Derren Brown, Lance Burton, John Carney, Mike Caveney, Raymond Crowe, Charlie Frye, Guy Hollingworth, Helder Guimaraes, Kevin James, Mac King, Martin Lewis, John Lovick, Max Maven, Eric Mead, Jeff McBride, Andy Nyman, David Roth, Juan Tamariz, Teller, Johnny Thompson, Suzanne, Paul Vigil, Michael Weber, David Williamson, R. Paul Wilson, Rob Zabrecky. If you have been in magic for any length of time at all, merely reading the name conjures up images of that person’s performing style. This is the importance of interpretation.

I’ve touched on the essays and the interviews, what about the tricks? As I mentioned above, there is just about something for everyone – card tricks, coin tricks, close-up routines, and magic for parlor and stage. I should mention most of these routines are designed for a formal presentation, like the Close-up Gallery or the Parlor of Mystery in the Magic Castle. They are longer routines, and some require the addition of extra “secret” stuff – like a servante for example. While this means you won’t be table-hopping with this repertoire, you will find routines that would work perfectly at the magic theaters that have recently sprung up around the country. I would not classify any of the routines as technically difficult, but they are not geared for the beginner – some magic experience is required. For those of you who love little gizmos and gadgets, you’ll find quite a few of them here; and you’ll probably have a delightful time sitting at your kitchen table putting them together.

And that’s about all I have to say about that. Please support this project; as you’ll hear in my conversation with David this month, producing a magic book is a labor of love. You simply cannot imagine the amount of time and effort that goes into it. Interpreting Magic has everything you want in a magic book: a wide variety of cool tricks, valuable essays, and insightful conversations with magic’s upper echelon of performers and creators. I give it my highest recommendation.

Interpreting Magic

Review by Nick Lewin (Vanish Magazine):

I loved David Regal’s 2008 book Approaching Magic, and have been eagerly awaiting his follow up to it. It has been well worth

the wait. Interpreting Magic is a superb book that will delight magicians everywhere with its premier content and expert execution. David is a brilliant and unique magical thinker, and when you couple that with his abilities as a wordsmith, you have a publication that exemplifies everything that is best in the magic world.

Interpreting Magic effortlessly covers every facet of magic. Whether you are looking for a fresh new sleight of hand routine or a hilarious stage effect you will find something exceptional here. It took David eleven years to publish this companion piece to his previous release, and the polish on these routines is a testament to taking the time to get things right. Today many people with

a good, but half-formed magical idea, release a video download that fails to do their idea justice. There is nothing that is served half-baked in Interpreting Magic. The toughest part of this book is separating the gems from the gems; this is a book that you will be dipping into and exploring for many years to come.

Interspersed with the moves, magic, and routines in the book are over 30 interviews with some of magic’s most respected “movers

and shakers” that inform and entertain in equal parts. I can not recommend this book highly enough for any genuine student of magic. Reading it will make you a better magician and performing the effects will make you a better performer. I give the book an enthusiastic five-star rating out of a possible five stars, but as an avid Spinal Tap fan, I have decided to make it a six. Books this good don’t come around very often, do not miss it!

Review by Norman Beck — M-U-M November 2019

What happens when you take a guy who has been in magic for over forty years, has a passion for the art, loves people, loves magic more, is clever past words, has a great command of the English language, is a comedy writer, knows everyone in magic, and lives near and works a lot at The Magic Castle? You get one of the best magic books ever. That is what David Regal has done here.

If you are into balloon animals and large illusions, Interpreting Magic is not for you. If you like anything else, you came to the right place; he has magic from simple to hard, short to long, and all points in the middle. Although there are a couple of things here that I don’t have the nerve to do (a couple that my personality could not sell like David can), I gained knowledge and joy from every page of this book.

One aspect of the book that has nothing to do with tricks is something he calls “A Conversation With…” He asked some very good questions of people like Simon Aronson Barry & Stuart, John Bannon, Gaetan Bloom, Eugene Burger, Derren Brown, Mike Caveney, Raymond Crowe, and a host of others.

The book is broken down into a card section, a card move chapter, close-up magic, cards and monte routines, effects with the Rainbow deck, stand-up, and stage. I found things that I loved in every chapter. The book is 553 pages long and my only critical problem with the book — and it is a major one — is this: it was too short. I was sad when I got to the last page. In fact, I started to slow my reading down toward the finish as I didn’t want it to end.

When I first met David years ago I formed an opinion of him that was wrong. His personality and his thoughts come out very clear in this book and the two words that come to mind are love and respect. At the end of the day, David loves his crafts both as a writer and a magician as well as a husband, a friend, and a father. The tricks are great but the man who wrote them is greater.

He shows love and respect for Ed Marlo and talks about how scared he was when he met him. He includes a trick that Ed did to cut the four Aces, which he got from Johnny Thompson — a very simple, very clever routine called Marlo’s Favorite Aces. Regal has a routine called Straight Face Aces that made me laugh out loud. I won’t tell you what it is, as I want you to get the same joy I got out of it.

My favorite item in the book was David’s Bottle. On a table you have a wine bottle with a cork in it and a playing card folded at the bottom. A card is selected and signed, it vanishes from the deck, he turns the bottle upside down, and the card falls into the neck. You remove the cork, take out the card with some forceps, open it, and it is their card. Now, you will have to work to do this but it is a very clever, fooling piece of magic.

A Cop Wallet is a Card-to-Wallet that is very clean, clever, and convincing and when you learn the method you will laugh. Lucky Number was one of my favorites. It uses a paper shredder to make the routine so funny. The paper shredder is the stand for the start and the thing that gets you in trouble. Very smart. That is what I caught myself saying a lot: “He is real smart.”

In the Bottle routine he says, “The result is a complete kinetic sentence that is deeply convincing.” I would tell you, “He just fools the shit out of you.” As you can see, he is much more sophisticated and erudite than I am.

The Survey is up near the top of the list as one of my all-time favorite effects. People are brought onstage, a deck of cards is handed out and shuffled, and four survey envelopes are removed. There is one for each person, so the first guy is asked, “Do you like cheese or pepperoni pizza?” They answer by spelling the word from the top of the deck. Each spectator has different, funny, entertaining questions that make the routine very commercial. At the end they all show their cards — they are the four Aces from a shuffled deck and they do all the shuffling and dealing. It is just great.

I loved the trick called Thank You, Dean — a tribute to Regal’s friend and great magician, Dean Dill. Four Kings are removed, the deck is cut into four piles, and a King is placed on each pile. The spectator puts a finger on one of the piles, and all four Kings are there.

The card move section had ideas that made me get out a deck of cards and try. The swindle control is one I would have liked to have not read but have been fooled by it first. The best I can recommend is either read it when you buy the book or go to Los Angeles and have David show you.

I confess that when I read Illegal Turn Control I thought any move that has “illegal” in the title I have to try. I found it hard to get down but it has many applications.

The Rainbow section is tricks with a deck in which all the backs are different. Think about this: The Queen of Clubs is at the face and the Ace of Spades is on top. The deck is spread face up on the table and you are told, other than the top and bottom card, you can have any card in the deck. Prior to selecting this you hand an envelope to a spectator. And there is no force. They pick any card form the deck; let’s say it’s the Two of Clubs. When they open the prediction it’s the Six of Hearts — and the magician is so excited! “A perfect match, the Two of Clubs and the Six of Hearts.” They look at you like you’re nuts, as that is not even close — until you turn them over and the backs match but all the rest of the deck are different backs. Not hard to do and very sneaky.

In the section on monte, the routine called Monte Python was very good but I had to look up the word “perspicacity:” The quality of having a ready insight into things; shrewdness. In Texas we would just say that David is a sneaky guy.

I often say things like, “You should buy this. You will like this.” Or some version of those recommendations. I liked this book as much as The Books of Wonder, the Stewart James books, and the Johnny Thompson books. I want to fly to Los Angeles and spend time with this writer. I can think of no higher praise for a book than to want to spend time with the writer.

Interpreting Magic

BY DAVID REGAL

REVIEWED BY JAMY IAN SWISS

David Regal and I might seem to have a lot in common. We both grew up in New York City and migrated to Southern California. We are both magicians who do close-up magic and stage magic, among other sub-genres of the conjuring arts. We are both writers—Interpreting Magic is the fourth major collection of original work that Regal has himself written. We have both produced instructional magic videos. We’ve both lectured to magicians internationally, and appeared at magic conventions, both major and minor. We both have IMDB pages, and have written and produced for television. We’ve both consulted for other magicians. And we’ve both been regular performers at the Magic Castle for decades.

But before you think that paragraph is intended to be self-aggrandizing, take note: When I look at Regal’s work, I feel like we have next to nothing in common. And that’s why our apparent similarities are of interest to me, and, more importantly, so very relevant to the contents of his new book, Interpreting Magic.

Regal set out for show business pretty early in life, becoming a regular performer in the New York based comedy troupe, “Chicago City Limits.” He moved to Los Angeles to be a real honest-to-goodness television writer, and his writing credits include major series like “Dharma & Greg” and “Everybody Loves Raymond.” (My IMDB page is different and far less impressive.) Not only that, but he’s also a bona fide comedy writer; I get laughs in my act, but Regal writes actual jokes. He’s also been the magic producer for the uniquely conceived “Carbonaro Effect,” now in its fifth season, where Regal has helped to create magic for hundreds and hundreds of segments for the show—and, without a single card trick. Oh, and his guy on “Celebrecadabra” won (which, if you were lucky enough to miss it, is about all you need to know about that project).

But wait, there’s more. Regal is constantly creating entirely new acts for his performances in the Close-up Gallery at the Magic Castle; one of those acts was done entirely with Rainbow Decks, and three of those routines are described in his new book. Ninety-nine percent of the magic I’ve published, lectured about, or marketed is based on sleight-of-hand card magic. Regal, on the other hand, is a damn inventor—he dreams up cool stuff, and then makes it. He thrives at arts and crafts, an aspect of magic I avoid whenever possible. Not only that, he invents and manufactures incredibly clever stuff, and then singlehandedly gets it manufactured and professionally packaged. And these are items that don’t get washed away in the flood of crap that is distributed in magic shops, but rather Regal’s stuff become greatest hits… effects like Sudden Deck and the Disposable Deck. Or, in some cases, his items are both so damned clever and popular—like the Clarity Box—that they get ripped off instantly, and internationally. I feel for the guy every time that happens. (And I’m not kidding. It’s infuriating to watch.)

So when I look at all that—all those strengths, skills, and accomplishments—I realize, indeed, it becomes abundantly obvious—that Regal and I have virtually nothing in common. And quite honestly, that just fills me with wonder, and respect, and on occasion, envy. (Okay, the Rainbow Deck thing not so much.) Don’t we all want to be a little more like Regal? I know I do.

And that, in many ways, is what Interpreting Magic is about.

Admittedly, this took me awhile to realize. At first I thought it was another Regal book—filled to the brim with clever and original material, from close-up card magic with an ordinary deck, to standup material that packs small and plays big, and can do first-rate service for corporate workers.

And believe me, there’s plenty of all that between the covers of Interpreting Magic. More than sixty routines, in fact, that also include comedy magic, mental magic, magic with coins, bills, finger rings, and more. The first trick in the book is a multi-phase, multi-effect card routine that requires nothing more than a couple of Elmsley and Jordan counts—you’ll read it, do it immediately, and then quite possibly add it to you repertoire.

In the close-up section there’s an assembly done with geodes (yes, geodes) that requires… more. There’s an easily constructed prop with which a signed card eventually appears in a dual photo picture frame. In what may well amount to the most extraordinary claim amid this review, there’s a routine with sponge bunnies that is capable of closing a formal close-up act, as the author did at the Magic Castle. This same section includes a superbly practical close-up pad/servante combination. There’s also a finger ring routine that contains an extraordinarily magical vanish that you’ve never seen before. I wish I had seen it before reading it as it would probably have fried me.

There are other clever do-it-yourself devices described, including a utility switching device utilizing a clipboard; a perfect quick bit of producing a wand from a card box immediately after removing an ordinary deck from the same box; a nice method for glimpsing a drawing or word written on one of a stack of business cards; and an apparently ordinary takeout coffee cup than can transform just about anything it will cover into something else entirely.

There’s an entire chapter describing four distinctly different monte-themed routines, all of which require double-stick tape. When you’ve ordered or picked up the book, buy a roll on your way home. These aren’t the only routines that require it. David Regal gets a lot of mileage out of double-stick tape.

In the standup and stage section there’s a comedy mental magic routine that is perfectly useable as is, but is also valuable if only for the way in which the prediction is revealed, and which could be readily adapted to other themes. There’s a new design for a card-in-wallet that you can make yourself (or purchase from the author) that provides a foolproof and speedy load into a zippered compartment by different means than the usual path of entry. There’s a utility switching device that is going to be worth the price of the book to someone, in which a folded card or bill is seen to be isolated in a clear wine bottle, and yet is switched out at the last moment with utter and absolute cleanliness (this would fool you if you saw it). There’s a signed-bill-in-impossible-location routine that fills the stage, is inherently comedic, utilizes an ordinary (if hilariously unlikely) assortment of nested props, beginning with a backyard trash barrel, and that will (and has) fooled well-posted magicians. And there’s a new take on the Tossed-Out Deck, in which the effect is (accurately) described by the author as follows:

A deck is examined and shuffled by a spectator. The performer places rubber bands around the deck, and it is sent into the audience where three people each peek at a card. The performer deduces the cards being thought of. The deck is never switched.

That version you’re doing kinda seems to suck now, doesn’t it?

This section also includes the complete details of the author’s device, routine and handling for the Linking Finger Rings. While he sells the device, the routine is among the better ones in the literature (and I say this as someone who has amassed more than twenty such routines in my research collection on the subject), and is worthy of careful study and consideration.

But here’s the thing: I haven’t gotten to the good part yet.

Interpreting Magic runs five hundred and fifty-three pages, describing “more than sixty routines for close-up, parlor and stage.” However, about two hundred of those pages contain no trick descriptions whatsoever. Rather, that third or so of the book’s contents is comprised of thirty-one “conversations” and interviews with professional magicians and magic creators, most or all of whom will already be known to readers.

Since my youth I’ve been a great fan of reading the introductions to magic books (as I’ve written about in the essay “Making Introductions” in Preserving Mystery). What often serves to render many introductions more timeless than the main content of the books they serve to introduce is that the introduction is the one place the author got to offer his opinions and thoughts about magic theory and performance. This has eventually changed, particularly since the early Eighties, thanks substantially to the writings of Eugene Burger. Burger freed up writers of magic books to range beyond mere trick descriptions, to explore theory, presentation, performance craft and more.

Along those lines, in Interpreting Magic the author scatters his own invaluable thoughts and opinions about theory, along with some funny anecdotes, into essays and other accompanying elements scattered throughout the book. This material includes commentaries about “Staging, Structure & Conditions,” “Plot,” an extremely important subject of finding and providing “Reasons” for every element and action present in your magic, and a distinctly confessional memoir piece. But in the thirty-one conversations with (mostly) professional magicians, each offers their own unique stories and perspectives, and their experiences and commentaries vary widely. Many of them, in response to the author’s questioning, provide accounts of the pathways they took in life and career, and what eventually rises to the surface is the realization—once you get past the origin tales of first tricks/shops/books/etc.—that the rest of the narratives are all so widely and wildly different. Gaudi said, “There are no straight lines in nature,” and clearly, neither are there any in the many paths to a career in magic.

Regal writes, “By reading the interviews that I’ve included in this book, I hope one can’t help but be overwhelmed by some commonalities shared by these performers and contributors to our art… All of them took steps, and proceeded with movement…. Even when the eventual destination was not clear, and the rewards were not immediate.”

But this lesson is only one of many to be mined from those two hundred pages of conversation. Read Suzanne’s thoughts on why you have to think carefully about when to look your assisting spectator in the eye, and why “You need to look when you know they are safe…” To read Teller’s thoughts on “action, passion and perception” in theater, or his thinking behind the construction of his routine for the Needles, is priceless, considering he has yet to write his own book of magic for us (House of Mystery and Germain the Wizard notwithstanding). Mac King, Martin Lewis, Lance Burton, David Roth, and Max Maven provided some of my favorite pieces here—your mileage will surely vary—sometimes for evocative historical anecdotes, other times for sheer laughs. I am sure I will pull this sizable volume from the shelf more than once in the future, more likely than not to re-read some of these contributions; while a few of these pages give off the inescapable whiff of self-promotion by the interviewee, most are filled with authentic personal revelation.

All of this comes in a well-produced volume, printed on glossy paper, illustrated with more than a thousand crisp color photographs, accompanying technical descriptions that are reminiscent in the clarity and personal immediacy of one of Mr. Regal’s great influences, Harry Lorayne (complete with sandwich tricks and indeed multiple versions of card assemblies that we—okay, maybe you—so deeply crave). Regal is also nothing if not diplomatic, not only occasionally in his approach to crediting, but also in his arrangement of the thirty-one “conversations” in alphabetical order. I told you he was a smart guy.

In his concluding thoughts, David Regal observes of his interview subjects that “What all have managed to do is contribute in ways unique to themselves,” and that “If you are reading this book, you are part of magic’s life. You form its present and inform its future.”

By thoughtfully considering these conversations and revelations—along with the fine magic described in the remaining three-hundred-plus pages—a book like this reminds us that each of us brings something unique to magic, to our personal interpretation, and to our particular experience in the art. Replete with explicit tales and advice born of real-world experience, this is a book that, upon considered reading, might well help to shape your particular present and future, and help inform you as to how to create your own unique part in “magic’s life.” If you consider the panoply of ideas in this book carefully, it cannot help but assist you in that quest.

“Love David new book” it a key strength of great knowledge! The menu of effects are just out of this world, the message with in the pages will open your eyes and mind about the spirit of the art of magic and what it means to the meny marsters magicians this joyfully book is fantastic big for it age! But if you like clean close up , stage effects and history and culture of the art of magic David put out some key things that will deliver some best effects that you will keep for a long time ! After reading this book the relationship you have for the art of magic will change! And you will become a master student !